Exploring Best Practices for Surgical Skill Training: Simulation Exercise in Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Technique with Medical Students

Exploring Best Practices for Surgical Skill Training: simulation Exercise in Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt Technique with Medical Students

Friday, April 21, 2023

Kristin Nosova, MD

Resident

Banner University Medical Center

Sacramento, California, United States

ePoster Presenter(s)

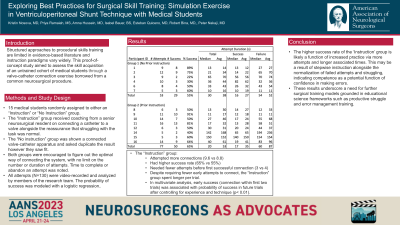

Introduction: Structured approaches to procedural skills training are limited in evidence-based literature and instruction paradigms vary widely. This proof-of-concept study aimed to assess the skill acquisition of an untrained cohort of medical students through a valve-catheter connection exercise borrowed from a common neurosurgical procedure.

Methods: 15 medical students were randomly assigned to either an “Instruction” or “No Instruction” group. The “Instruction” group (N=8) received coaching from a senior neurosurgical resident on connecting a catheter to a valve alongside the reassurance that struggling with the task was normal. The “No instruction” group (N=6) was shown a connected valve-catheter apparatus and asked duplicate the result however they saw fit. Both groups were encouraged to figure out the optimal way of connecting the system, with no limit on the number or duration of attempts. Time to complete or abandon an attempt was noted. All attempts (N=130) were video-recorded and analyzed by members of the research team. The probability of success was modeled with a logistic regression.

Results: The “Instruction” group attempted more connections (9.6 vs 8.8), had higher success rate (65% vs 55%), needed fewer attempts before first successful connection (3 vs 4). Despite requiring fewer early attempts to connect, the “Instruction” group spent longer per trial. In multivariate analysis, early success (connection within first two trials) was associated with probability of success in future trials after controlling for experience and technique (p < 0.01).

Conclusion : The higher success rate of the ‘Instruction’ group is likely a function of increased practice via more attempts and longer associated times. This may be a result of stepwise instruction alongside the normalization of failed attempts and struggling, indicating competence as a potential function of confidence in making errors. These results underscore a need for further surgical training models grounded in educational science frameworks such as productive struggle and error management training.

Methods: 15 medical students were randomly assigned to either an “Instruction” or “No Instruction” group. The “Instruction” group (N=8) received coaching from a senior neurosurgical resident on connecting a catheter to a valve alongside the reassurance that struggling with the task was normal. The “No instruction” group (N=6) was shown a connected valve-catheter apparatus and asked duplicate the result however they saw fit. Both groups were encouraged to figure out the optimal way of connecting the system, with no limit on the number or duration of attempts. Time to complete or abandon an attempt was noted. All attempts (N=130) were video-recorded and analyzed by members of the research team. The probability of success was modeled with a logistic regression.

Results: The “Instruction” group attempted more connections (9.6 vs 8.8), had higher success rate (65% vs 55%), needed fewer attempts before first successful connection (3 vs 4). Despite requiring fewer early attempts to connect, the “Instruction” group spent longer per trial. In multivariate analysis, early success (connection within first two trials) was associated with probability of success in future trials after controlling for experience and technique (p < 0.01).

Conclusion : The higher success rate of the ‘Instruction’ group is likely a function of increased practice via more attempts and longer associated times. This may be a result of stepwise instruction alongside the normalization of failed attempts and struggling, indicating competence as a potential function of confidence in making errors. These results underscore a need for further surgical training models grounded in educational science frameworks such as productive struggle and error management training.